Kamchatka, Russia: Flyfishing the Nikolka

Fish God Of Kamchatka River

“Kamchatka’s 108 volcanoes resemble the fossilized vertebrae of one of the enormous brown bears that haunt this mix of virgin forest, glaciers and salmon filled rivers.”

Achivinsky Volcano, Petropavlovsk

“Bezymianny, however, is not the only bad actor on this long peninsula.”

Ancient Farm Milkova

“The forest track cuts through volcanic ash deposited by ten thousand years of volcanic eruptions and repeatedly fords pools covered with skim ice.”

Yuri Ponomarev on a Pole Boat

“Pulling on rubber boots and a camouflage army jacket, Ponomarev is five foot eight, black haired and thin with currents of gray showing in his thick beard.”

YURI PONOMAREV and his nephew

“‘Tomorrow the weather will clear,’ he continues. ‘We will fish the Nikolka and you will see how good fishing in Kamchatka can be.’”

Ingo Skulason making a roe Sandwich

“On this empty river, a boat is worth a fortune and life is cheap.”

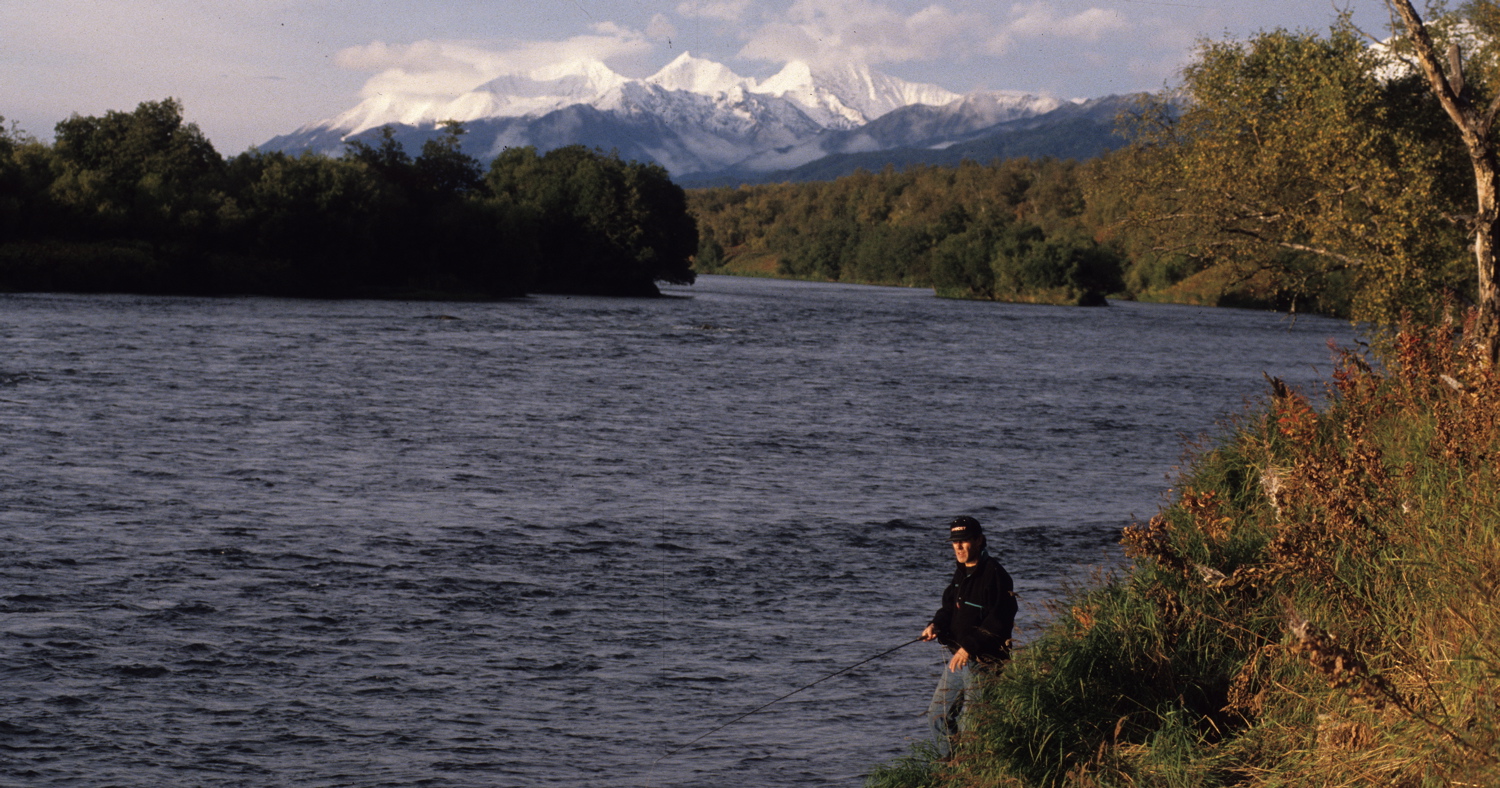

Kamchatka River In The MORning

Yuri's Camp on KAMCHATKA RIVER

“With Ingo translating he tells me, ‘To catch a Russian Salmon you must use a Russian Spoon…’”

Andre Gidkov FISHing KAmchatka River

“A second later the six weight rod bends violently toward the water and my trout reel sheds line in a prolonged shriek.”

Kamchatrybvod Fish Camp

“Beating against the current, the two boats slowly moved upstream…”

Historic Petropavlovsk

Yuri's Bagna

“That night we lighted a fire in the tepee and, surrounded by the ghosts of Plains and Kamsidal Indians, we praised the Nikolka”

INGO SKULASON Fishing Kamchatka River

I was casting a red fly to a Silver Salmon when Ingo Skulason, pointed to the ancient cedar coffins. Excavated by Eastern Russia’s Kamchatka River three had broken open spilling their contents into the water. Two others, however, protruded from the gravel bank where, balanced precariously between the overlying meadow’s dense thistles and the resting salmon, their square ends had been knocked off exposing the leather shoe soles of the long dead occupants.

An Icelandic businessman now living in Petropavlovsk, Skulason was well acquainted with the brutal history of the thorny meadow. By 1743, Cossack soldiers had explored the Kamchatka Peninsula south to the present village of Milkovo. Chancing upon an indigenous Kamsidal Indian village, they first shot the men then enslaved the women who proved to be fatally susceptible to leprosy. The disease quickly decimated the Kamsidals and hoping to isolate the population, Russia exiled its own lepers to the outpost.

If you did not notice the emerging coffins you could not guess what lies beneath the thistles. No stones or weathered wooden plaques mark the graves and it is unlikely that the Cossacks wasted coffins on leprous Indians. The leather shoes belonged to either the soldiers, or Russian lepers.

Andrew Fishing Kamchatka River

Located on Russia’s Pacific Coast on a north south line from the Russian Kurils and the Japanese Island of Hokkaido and filled with volcanoes and geysers, the Kamchatka Peninsula is the world’s most active thermal area. With Iceland and Yellowstone National Park placing a distant second and third, Kamchatka’s 108 volcanoes resemble the fossilized vertebrae of one of the enormous brown bears that haunt this mix of virgin forest, glaciers and salmon filled rivers. Rising to a maximum of 15,000 feet, the snow-covered cones add structure to this 750-mile peninsula that divides the Bearing Sea from the Sea of Okhostsk. Though most have not erupted in hundreds of years, twenty-nine others tremble with life.

In May of 1997, a torch of hot magma that wavered beneath Kamchatka’s tectonic fault touched the 9453-foot Bezymianny. Following a series of seismic shakes, the volcano blasted a 45,000-foot plume of ash into the stratosphere. Bezymianny, however, is not the only bad actor on this long peninsula. There is Avachinsky–the perfect, 9000 foot cone which towers above Petrapavlovsk. Following a 45-year slumber, Avachinsky suddenly startled awake in January of 1991. No seismic warning or towering column of pyrotechnic ash signaled the devil’s work below. Avachinsky simply stretched and stuck out an incandescent lava tongue at the nervous city.

Bezymianny VOLCANO, Kamchatka, Russia

Two hundred miles north of Petropavlovsk, the salmon appear in late August. Starting as a whisper, their numbers rapidly grow in volume until the river pulses with Silvers, Chums, Sockeye and Kings flooding against the current. The territorial Silvers are filled with a biological imperative that causes them to attack the red streamer when it drifts too near. I cast into the head of the pool then mend the line to prevent it from dragging in the current. A moment later a coho slashes at the fly and, when it feels the hook, bends my trout rod to its breaking point. As the coho races downriver, I find it difficult to concentrate on the fight. I keep glancing at the leather soles and when the autumn hued buck turns on its side, I release it, climb out of the river and scale the bank. I can’t say what perverse curiosity drives me to my knees at the end of the rough, cedar box. And, I can’t explain why I start to scrape the sand out from around the shoes.

After two and a half centuries, the coffins might contain a few bones or scraps of cloth. Excavating around the leather soles I see the blackened bones of a foot and beyond that a slender tibia. Staring at these relics of Kamchatka’s violent history, it occurs to me that desecrating any grave, much less a leper’s grave is a bad business and I quickly stand, brush my hands off and wade back into the river.

Road To Kamchatka River

It has been four days since Ingo Skulason, his assistant Andre Stepanchuk and I turned off Kamchatka’s main north south road onto a rough forest track that led to Yuri Petrovich Ponomarev’s fishing camp. At two in the morning the headlights showed the effects of three days of alternating rain and snow. The forest track cuts through volcanic ash deposited by ten thousand years of volcanic eruptions and repeatedly fords pools covered with skim ice. Ingo observes that with any more rain, we would need an Akoosh, one of the massive track vehicles used by Kamchatkans to assault the back country when the roads fall apart.

I had met Ingo the previous winter while helicopter skiing on the Mutnovsky and Vilyuchensky volcanoes that rise south of Petrapavlovsk. Mutnovsky was active, Vilyuchensky was not and the skiing was a rare mix of 7100 vertical feet perfect snow, tinted yellow by sulfur fumaroles. A few minutes before I boarded the flight back to the U.S., Ingo said, “You should come back and fish for salmon and rainbow trout. It will be like nothing you’ve ever experienced.”

Now at two a.m., Andre follows a labyrinth of right and left turns through the dark deciduous forest until we reach the rutted end of the road. “So, we have finally arrived here.” He observes in lightly accented English.

YURI PONOMAREV's camp

The October night air was clean and cold and with Andre leading, we shoulder our duffle bags, switch on our flashlights and follow a trail into the woods. Emerging from the birch, aspen and alder trees into a park like clearing, we discover two cabins, a sauna decorated with a weathered moose head, an open gazebo and, paradoxically, a Plains Indian tepee. Ingo crosses to one of the cabins and hammers on the door. He is answered by a deep voice shaking off sleep. A moment later, Yuri Ponomarev appears.

Pulling on rubber boots and a camouflage army jacket, Ponomarev is five foot eight, black haired and thin with currents of gray showing in his thick beard. He looks to be in his early fifties but could be younger. Until he was forced into retirement by Russia’s inability to pay its employees, he worked as a biologist for the Kamchatka Department of Fish and Game. Though he originally intended the two log cabins, tepee and sauna to serve as a retreat for friends, the near collapse of the Russian economy has taken a toll on all Kamchatkans and he is now forced to use the camp as a base for subsistence hunting and fishing.

Offering a strong, calloused hand, Yuri leads us to the hexagon shaped log gazebo. A bench covered with thick caribou and moose skins blankets the outside wall and he gestures for us to sit then stokes a wood fire on which he sets a pot of fresh salmon soup. He then places a plate of red caviar, fresh bread and butter on the table. We eat well then retire to the log cabin for a few hours of sleep before dawn.

“Tomorrow the weather will clear,” he continues. “We will fish the Nikolka and you will see how good fishing in Kamchatka can be.”

Springing from the flanks of Bezymianny’s 15,000-foot volcanic massif, the 466 mile long Kamchatka River once supported the world’s most prolific salmon runs. A combination of catastrophic over fishing and unregulated logging, however, devastated the fishery until today, though the salmon are abundant, their numbers are down from earlier, record years. Yuri related how, by stringing gill nets from bank to bank, local fishermen would harvest 100 tons per season from a single hole.

Dawn’s first light revealed Kamchatka’s hard wood forests were tinted with the faint reds, yellows and oranges of the coming fall. To the north the volcano blue glaciers ringed Kijucevskaya’s 15,438-foot cone. In front of the camp, the Kamchatka River is spotted with the rises of Mikisha (Rainbow Trout) and Harius (Grayling). Up since before dawn, Yuri studies the river while he brews coffee on a wood fire. During the past month the meandering current had excavated the bank below camp and now threatened the bagna. If the river continued to undermine the bank, Yuri would have to jack the bagna onto skids and block and tackle further into the forest–an eventuality he accepts with a stoic shrug.

Following a breakfast of bread and red caviar, Ingo and I climb into Yuri’s battered metal boat. The smoking outboard rattles in protest as we turn downstream toward where the Nikolka joins the Kamchatka. We have traveled less than fifteen miles when we come upon four hunters dragging a skiff around and over the submerged jigsaw of ash, birch and aspens that choke the bank. They tell us they had exploded their outboard three days before and have been poling upstream ever since. When they ask for a tow, to my surprise, Yuri refuses.

Driftwood Talisman, Kamchatka River

Tired, wet and heavily armed the hunters are clearly angered by his reply. There are sobering reasons why Kamchatka is known as the Wild East. On this empty river, a boat is worth a fortune and life is cheap. In the silence that greets Yuri’s refusal, one hunter shifts his rifle until it points at the water between us. The threat is as palpable as the pungent cigarette smoke that drifts in the cold morning air.

Yuri refuses to be intimidated. Informing the four that we are on our way to fish the Nikolka, he promises to give them a tow when we return upriver. That’s the best he can do. Take it or leave it.

Either fishing the Nikolka or the promise of help placates them. They agree to wait and, when I last see them, they are poling upriver through the chaotic dead fall.

There is no mistaking the Nikolka . One minute we are being pushed downstream by the Kamchatka’s gray green current, the next turning up a huge, effervescent spring bubbling out of a gravel base. As the boat pushes against the current, its shadow sweeps across huge schools of salmon which scatter in all directions.

Flowing east 240 miles from the mouth of the Kamchatka, this nine mile long tributary offers undisturbed spawning grounds for both early and late run sockeye and cohos. Along with the vast numbers of salmon, hundreds of thousands of char, grayling, and rainbow trout shelter in the Nikolka’s deep, clear holes and along it’s heavily wooded banks.

INGO SKULASON And Yuri Ponomarev

Yuri tells me that this isolated river may see one or two anglers all year–if that. “And never one who fishes with these….” he gestures dismissively toward my boxes of hair patterns, leeches, nymphs and dry flies.

With Ingo translating he tells me, “To catch a Russian Salmon you must use a Russian Spoon,” and offers a choice. Tea, table or soup. To make a Russian Spoon you first saw off the handle, file off the rough edges and drill holes for a swivel and hook. Then you heave it into the dark schools of salmon that hang above the bright gravel bottom. The effect approximates a bomb exploding among them. Yuri must hope that sooner or later one of the big hook jawed males will grow irritated. And when it does, turn and snap at the spoon.

If Yuri Petrovich Ponomarev was skeptical of my flies, while I caught dozens of eighteen inch Harius (Grayling) , he got skunked. In time he challenged me to catch a Kishush ( a Coho Salmon), “For this you must definitely need a Russian Spoon,” he insisted, selecting the brightest from his box.

I told him, before the spoon, I wanted to try a black leech with silver bead eyes–chenille and feather talisman I’ve had success with in still water. Dropping it in front of a dozen salmon, I watch three large fish break from the dark pod and follow. On my next cast, a smaller fish inhales the fly. A second later the six weight rod bends violently toward the water and my trout reel sheds line in a prolonged shriek.

Yuri is visibly impressed. “But you will not land this Kishush,” he tells me. “Not with that little stick of a rod and toy reel.”

ANDy, Nikolka River

But I did land that coho and a half dozen more. At one point, I caught Yuri watching with wonder as four salmon followed the fly. But he was a proud man and would not ask to borrow the fly rod. Instead I pressed it upon him, quickly taught him a basic cast and watched while he laid a Gray Wulff in front of a dozen rising Harius. One rose to the fly and raising the rod tip, Yuri set the hook. He caught four more, then nodded, smiled with gratitude and handed the rod back to me.

When I indicated he should continue he said he wanted me to try a tributary where Mikisha (Rainbow Trout) were rising to hatching caddis. Tying on an Elk Hair Caddis, I cast it into the quiet water next to a riffle. A large rainbow rose to the fly and when I lifted the rod tip and set the hook, the big trout exploded past me and raced downstream. I managed to turn it in the current and gradually fought it back to my waders. It was twenty inches long, by Kamchatka standards a nice fish, but not huge–certainly not one of the eighteen pounders that Yuri claims haunt this river. Studying the thousands of spawning salmon, I had no doubt that these behemoth Rainbows had grown fat on roe and during the spawn would not waste energy on dry flies.

Russian Fish & Game

During the next hour I caught and released a dozen Mikisha and Harius and when the hatch faded I joined Ingo and Yuri in a meadow in front of the Kamchatrybvod fish research station. Periodically inhabited by Fish and Game Biologists conducting fish counts, the cabin was now deserted and we shared a lunch of smoked salmon. The sun was setting behind Kijucevskaya’s glacier ringed cone when we returned to the boat and followed the Nikolka out to its confluence with the Kamchatka. Turning upstream the ancient outboard rattled obscenely as it slowly pushed the boat against the stiff current.

It was growing dark when we encountered the Russian hunters. They had covered three miles since morning and when we pulled alongside and offered them a rope, their expressions revealed a mix of relief, exhaustion and gratitude. We had not seen another boat all day. Nor, would we see one all week. It was Yuri’s outboard or nothing and now, doubly burdened it screamed and rattled and smoked in protest. Beating against the current, the two boats slowly moved upstream to an isolated gravel beach where the hunter’s friend had waited three days for their return.

The hunter’s thanks took the form of vodka toasts and numerous hugs and it was well after dark before we arrived back at camp. Andre and Yuri’s friend Andre Gidkov were preparing a dinner of partridge soup, smoked salmon and caribou steaks and while the meat broiled over a wood fire we adjourned to the bagna. Similar to a sauna with a distinctly Siberian character, the bagna’s bare wood benches were blistering hot. We sat on felt blankets and threw cold water scented with birch leaves on heated rocks which sent clouds of steam billowing through the small room. And when the heat became oppressive we dipped birch branches in cold spring water and whipped our shoulders and chests.

That night we lighted a fire in the tepee and, surrounded by the ghosts of Plains and Kamsidal Indians, we praised the Nikolka –the Kishush, Mikisha and Harius. Between courses of caribou and salmon, cheese, berries and forest greens, we toasted the fish, Kamchatka and the U.S.. And at a silent moment when we were staring at the fire, Ingo translated. “Yuri thinks you should come back,” he said. “He thinks you should fish the Nikolka in October when the big Mikisha will take your flies.” Though Yuri spoke no English, he nodded in agreement. “And then when your arms cramp from reeling the heavy Mikisha in, we will get horses and circumnavigate Kijucevskaya. It will take a week and you will see wildlife, and geysers, bears and moose, the full color of the leaves and yes, many, many fish….”