Switzerland: Flims Laax, The White Arena.

I was engrossed in a trail map of the White Arena that showed two vast bowls––both of which were serviced by an interconnected web of trams, chairlifts, gondolas and T-bars.

I should strike the word “wait” from my vocabulary. With one week to explore the White Arena, time was burning. The only thing waiting was a finite number of runs that was rapidly shrinking while this storm stalled above the resort.

I saw alpen glow on church spires, crumbling castle ruins above the Rhine and might have gone on indefinitely reading Flims and thinking Films if a conductor on the connecting train from Zurich to Chur hadn’t pronounced it.

In Flims, the midday meal approximates communion where, a few minutes before noon the restaurants fill, wine starts to flow, bread appears, an entree is ordered and before a second Coffee Williams has grown cold, shadows begin to grow and a planned 10,000-feet of vertical has faded to a rose-colored 2,500.

My last run was down a narrow cat track that led back to Flims Waldhaus. On that blue-sky day I couldn’t make a wrong turn, miss a pole plant or lose an edge.

Sagging herders’ huts lie scattered beneath Naraus and the ruins of an Eight Century castle are hidden in the woods above Fidaz. New apartments, stand hip to gable with three-story farm houses, where cattle low from a ground-level barn and the scent of fresh hay and manure fills the street in front.

My first mistake was skimming a brochure on the Swiss Grisons. If I had paid more attention to the text I wouldn't have reversed the "l" and the "i" in Flims. Psychologists use “metathesis” to describe this correctable learning dysfunction. In my case the switch took. At the crux when I should have corrected my mistake, I was engrossed in a trail map of the White Arena that showed two vast bowls––both of which were serviced by an interconnected web of trams, chairlifts, gondolas and T-bars- soaring six thousand vertical feet above Films. If I hadn't exactly discovered Films, I was certainly the first on my block to hear about it. With the unbiased conviction more common to children and St. Bernards, I marveled at this convenient match of area and name. What could be more perfect than a resort named Films? Even as I cleared security and boarded Swiss Air, I continued blithely along, carefully adding pieces that fit this puzzle while hammering in those that didn't until I had a neat mental package wrapped in the red and white of the Swiss Flag.

Wined and dined into semi-consciousness on the flight to Zurich I dreamed of Films’ mountain guides and Heidi’s blonde granddaughter cutting figure achts in powder schnee. I saw alpen glow on church spires, crumbling castle ruins above the Rhine and might have gone on indefinitely reading Flims and thinking Films if a conductor on the connecting train from Zurich to Chur hadn’t pronounced it.

“Next stop Chur.” He had read my ticket and now glanced at me and added, “This is the connection to Flims.” Only then, when the train slowed for the platform did my beautifully wrapped Swiss package come unglued.

Why Flims? Or, for that matter, why Switzerland? Why wonder over a strange language, different food and customs when you could ski the Western Rockies and forgo the surprises? Exactly for those surprises! There is something about Switzerland’s vertical Alps, crystalline air, chiming church bells and incredible skiing that leaves you touched by magic.

But there was no magic the evening I arrived in Flims. Stepping off the bus, I was pelted with sleet that quickly changed to wet snow. Surrounded by those silent, unrelenting flakes my first impression of Flims was a narrow main street fronted by small hotels, ski shops, small, candlelit cafes and, beyond that, a thickly wooded hillside that faded into the gathering storm. No mountain, no guides, no Heidi . . . just half a dozen locals hurrying home under black umbrellas and the sound of chains clanking on wet pavement.

"Welcome to Flims," I said, pronouncing it correctly, for the first time. Ankle-deep in slush, I wondered where I had gone wrong. Six thousand miles and a full day's travel all to reach this quiet corner of Switzerland.

Neil Boulton, the Australian porter from the Waldhaus Flims Hotel, arrived, heaved my bags into the hotel SUV and fishtailing through the slushy streets inquired, “You here for the week?”

“That’s the plan.” I watched wet snow freeze on the windshield.

Flims, the resort, consists of a number of small towns straddling a secondary road that loops onto the glaciated plateau rising above the head waters of the Rhine River: Flims Waldhaus, Flims Dorf, Flims Falera and Flims Laax.The last three serve as gateways to the White Arena; Waldhaus is the older summer resort where most of the large hotels can be found. Flims Laax has long enjoyed a reputation as a fine summer resort. Hiking paths break through the woods to the open meadows above. Tennis and horseback riding, swimming and boating in high alpine lakes have long been a draw here. Local hotels have always figured heavily in economic decisions and without their support the first wooden chairlift from Flims to Alpe Foppa would not have been built. The connecting lift to Naraus was completed two years later in 1947. But it was not until 1956 that the tram, which soars to Cassons Grat, was finished. This opened the vast snowfield above Flims Dorf and served as a major first step toward the region's present status as a world-class winter resort. From then until the mid-seventies, however, little more was added. Then, Vorab and La Siala peaks erected 21 lifts that more than tripled the number of lift-serviced acres

"Bloody awful weather," Boulton followed the main street toward the hotel. "Makes everything a mess. I could hate it but for what it does for the skiing."

"And how has that been?" I prayed for an optimistic forecast.

"Nonexistent. This storm closed everything above the beginner piste,” He said. “But you couldn’t have picked a better time of year. Once the visibility returns, the skiing will blow you away.”

“And how has the season been so far?”

“Amazing. You’ll see.”

And that's where it was left through that night. "Unfortunately the entire mountain is closed," Elsy Maciak explained in perfect English the next morning at the Flims Waldhaus tourist office. "Much of the White Arena is above tree line. Today, severe winds have raised the avalanche danger. You must wait for finer weather."

“Wait?” I wish I could strike the word from my vocabulary. With one week to explore the White Arena, time was burning. Hidden in the gray mist that swirled around the tourist office, the only thing waiting was a finite number of runs that was rapidly shrinking while this storm stalled above the resort. Each minute translated into forty missed turns, each hour four thousand missed vertical feet. Wait?

"Of course there are two beginner runs, but you wouldn't ... "Elsy voice trailed off as I opened the door and stepped into the storm.

The chairlift from Flims Dorf to Naraus, 2,400 feet above, is a sideways affair that seems to run across the flats more than up any significant face. If blowing snow combined with nonexistent light made me question whether discretion is the better part of valor, my first turns below Naraus confirmed it. When the light fades off-piste in the White Arena moguls announce themselves as solid shocks to your knees, rock faces simply drop away, up becomes down, and even expert skiers revert to a beginner's snowplow as a talisman against things that go bump in bad light. In this inverted world I had my first taste of the White Arena and the taste was bittersweet.

The snow was exquisite––cold, feather light, whispering past my knees with each edge change. And while I couldn't see further than my tips, the skiing was unbelievable. If prayers could petition nature, those clouds would have melted away opening the vast bowl above for the ten skiers crazy enough to search for satisfaction in the teeth of this storm.

In Switzerland, however, man does not live by vertical alone. That night, while the storm turned larch pines into conical white ghosts, I dined on crab and avocado appetizers, double consommé soup, butter lettuce, watercress and shredded radish and carrot salad, grilled veal steak for an entree, and for dessert a meringue ice-cream cake covered with whipped cream.

Built in 1880 the Waldhaus Flims Hotel is surrounded by century old pines, maples and ancient locust trees. The Hotel’s five-star rating guarantees service and service again, gourmet dinners, fresh linen and silver and, if you have the strength after skiing seventy thousand vertical feet in the White Arena, indoor swimming, tennis, curling, a sauna, three restaurants and two night clubs. It is a little extravagant and a lot self-indulgent––everyone should experience it once in life.

Dawn arrived as gray and unpromising as the morning before. Waiting for a blizzard to blow itself out is agonizing at best. What do you do on another gray day in paradise? Over a breakfast of warm croissants, soft-boiled eggs and muesli(a delicious combination of oatmeal, cream and fruit), I guessed I could take a day trip up the canyon to Davos or down it to Andermatt. But as I drained the last of my third cup of coffee, sunlight exploded across the herders' huts below Naraus.

Half an hour later, I boarded the gondola from Flims Dorf to Startgels. The snow had stopped, but clouds still hung like a gray veil across the face below Cassons Grat. Lifts were opening and I hurried with twenty others to make a quick transfer to the Brauberg tram that climbed through the thinning overcast. Mist swirled around the tram; the sky grew progressively lighter, then opened to reveal the brilliant sweep of the White Arena.

One turn in the new powder below La Siala sent a signal to the cerebral recorders that this would be a magic day. In an area this large, when in doubt, don't. Unfamiliar with the runs, I could see how it would be possible to ski off one of the cliffs above Startgels. In some spots a foot of new powder could trigger a major slide. Like most European resorts, Flims has a let-the-skier-beware attitude. Skiers are permitted to explore the terrain, but with the avalanche danger off the scale, most skiers that day stuck to the groomed runs, tracking to the farthest packed boundaries but no further. Those caught in off-piste avalanches are dismissed sadly as "stupid" or "crazy."

Rules and restrictions all noted, I confess greed made me do it. That and thirty-six hours waiting for visual flight rules into the White Arena. Tempted by those unskied acres between the wandering pistes above Nagens, I risked a dozen untracked turns. The powder was silky soft and forgiving, flowing past my shins in an airy, crystal stream.

Oblivious to the disapproving glances of a couple skiing next to me on the piste, I arced into a shallow swale, up one side and out the other, back onto the groomed, thought “to hell with it” and dived back into the powder.

The White Arena is far too vast to attempt in one day. In fact it is not one area but three connected by sinuous traverses. Each peak is different from the next and each would deserve a day alone to sort out even the most obvious lines down open faces or next to the trees.

La Siala is the center of three peaks with the left hand known as Vorab and the right called Cassons Grat. Below La Siala many of the runs lack the pitch and vertical of Western U.S. resorts. Instead they are wide, intermediate trails that snake across the rolling hills. But below Alp Nagens there are steeps that take your breath away as your tips rock over the transition. And below Berghaus Nagens there are others that will suck your legs dry. At a little over nine thousand feet La Siala can be reached by a chairlift or by one of three T-bars crossing undulating flats. Each night a fleet of snow cats irons the miscellaneous bumps and wrinkles out of the hill, leaving behind a perfect playground for shaped GS skis tuned to cruise.

Vorab, the highest of the three peaks and a stable glacier, is skiable year-round. A double T-bar services its rounded summit and skiers have a choice of a rolling intermediate run off the face or a back-side expert face which drops 3,500 feet to a double chair at Midada Sut. This chair rises to Crap Masegn where a transfer to a gondola will bring you back to the glacier. On that same ridgeline, Crap Sogn Gion serves as hub to a spoked series of runs and returning lifts.

The eighty bed Berghotel, complete with indoor swimming pool, gym, bar and two restaurants, is located here, as is the start of an FIS approved downhill. From Crap Sogn Gion a variety of runs drop to wander through the wooded faces below, ending, at either a T-bar 2,000 feet below in Curnius or1,000 feet and a double chairlift below that in Larnags. This is some of the best skiing Flims Laax offers––wide open runs that are marked by consistent moguls. Weekdays in midseason skiers can count on minimal lines and empty runs.

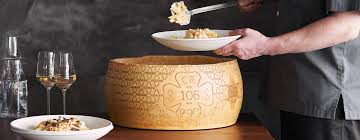

Served at any one of ten mountain restaurants, a Swiss lunch approximates communion. A few minutes before noon the restaurants fill, wine starts to flow, bread appears, an entree is ordered and before a second Coffee Williams (coffee with pear brandy) has grown cold, shadows are beginning to lengthen and a planned 10,000-foot of vertical has been reduced to a rose-colored 2,500.

My last run was down a narrow cat track that led back to Flims Waldhaus. On that blue-sky day I couldn’t make a wrong turn, miss a pole plant or lose an edge and a little tired and hugely self confident, I went around a ski instructor and his dozen students, pointed my skis toward what appeared to be a flat meadow and never saw the mogul that sent my left ski spinning off in a peripheral arc. The next bump took my right ski, and the series following stripped me of my poles, hat and goggles.

The instructor, a small man with a gold earring, retrieved my equipment and in Swiss German––a language that sounds like two cups of German, a dash of Italian, a tablespoon of French politely advised me to slow down. Most Swiss speak English and though most in that English speaking majority will modestly deny any but the most rudimentary knowledge, following that disclaimer they will take a dinner order, sell you a Rolex watch, accept a deposit for a numbered account or explain how to travel from one end of Switzerland to another.

Main street should not define a resort and that is certainly true of Flims. If its business face showcases sport and clothing stores, jewelers, restaurant and bakeries, along the back streets you will discover the true character of this village. Here century old houses bear the intricate white calligraphy of old world blessings, sagging herders’ huts lie scattered beneath Naraus and the ruins of an Eight Century castle are hidden in the woods above Fidaz. New apartments, sparkling with fresh paint, stand hip to gable with three-story farm houses, where cattle low from a ground-level barn and the scent of fresh hay and manure fills the street in front. This is the traditional Flims, the side tourists too often overlook.

On my next to last night I took a horse-drawn wagon from the Waldhaus Flims Hotel into the foothills above Laax. As the horse hoofs beat time on the snowy road, I watched the clouds scud across a crescent moon while the countryside passed in alternating dark forests and bright meadows. When the road ended my driver handed me a torch and pointed to a path that disappeared across the hillside. It took fifteen minutes to reach the Tegia Larnags, an old mountain hut off the main ski trail that had been converted to a restaurant. I doused the torch, opened the heavy wooded door and was greeted by the family’s Bernese Mountain Dog, who, with a little help from my host, showed me to a table.

Dinner opened with fresh salad, walnut and raisin bread and continued with geschnetzelles, minced veal in crème sauce served with rosti, a traditional fried potato dish.

Guest continued to filter in while I lingered over coffee. A man pulled his accordion from a worn case, played a familiar scale, tapped his foot once and squeezed the first bars of a song that all the guests knew. While dancing can be found in Waldhaus Flims, that night I preferred a Coffee Williams, a happy accordion and willing crowd. Much before the first week ended, I found myself winding down. “Going native” is the tropical equivalent. “Getting Laaxed” belongs to these crystalline alps.

I didn’t intentionally save the best for last. After exploring Vorab and the woods below Crap Sogn Gion, I thought I’d seen everything. But the face below Cassons Grat was a secret waiting to be discovered. From Flims Dorf I took a forty-minute combination of chairlifts and trams to reach the exposed ridgeline where the tram station huddles in a rocky swale out of the wind. I climbed another one hundred and fifty vertical feet to reach the top of the chute that plummets to the bowl below. Sweat soaked my polypro by the time I broke out on the eight thousand foot ridge where the Grissons glowed like Stuben glass across the Rhine River.

Half a dozen tight turns led me to an unbroken face that dropped mogul free twenty six hundred feet back to Naraus. Successive warm days followed by freezing nights had settled the powder, creating a hard, unbreakable surface. A silky layer of corn now lay on the January snow and I linked turn after turn just to feel my skis bend.

Vertical evaporates too quickly when one turn leads to the next. The wind whistled past my ears and my eyes started to water as I realized that these are the visual credits I needed to save in a memory vault. Moments when the vistas amounted to a physical assault on my senses—when the language, sights and smells short-circuit critical thinking.

That’s why Flims. Because more than a million digital pixels, or frames per second, I value the mental exposures. Even an amateur photographer knows there are only a few rare places where you can’t take a bad picture.